Written by:

Last Updated:

May 29th, 2025

At the turn of the 20th century, America was introduced to a new wonder drug – cocaine. It was widely heralded for its medical virtues, offering relief from several ailments, from toothaches to depression. However, the initial enthusiasm lasted just a few short decades as cocaine’s addictive properties became apparent and its misuse widespread. Everyone from esteemed medical professionals to world-famous scientists fell under its sway until public outrage and sensational media reports began to turn the tide. This shift set the stage for America’s first substantial narcotics crackdown and, at least for the next fifty years, its most successful war on drugs.

In this exploration, we will delve into the turbulent era of cocaine’s rise and demise, examining the people, panic and policies that shaped the nation’s response to a growing drug epidemic.

The rise of cocaine in America

Cocaine first graced the American shores in the latter half of the 19th century and was immediately touted as a miraculous cure-all due to its stimulating properties. Initially imported in small quantities for medical research, it wasn’t long before its use became widespread in the medical community. Physicians prescribed it for a plethora of conditions, ranging from morphine addiction to chronic fatigue and as a local anaesthetic for surgeries and dental work. This medical endorsement, however, was not accompanied by an understanding of the drug’s addictive nature or its potential for harm.

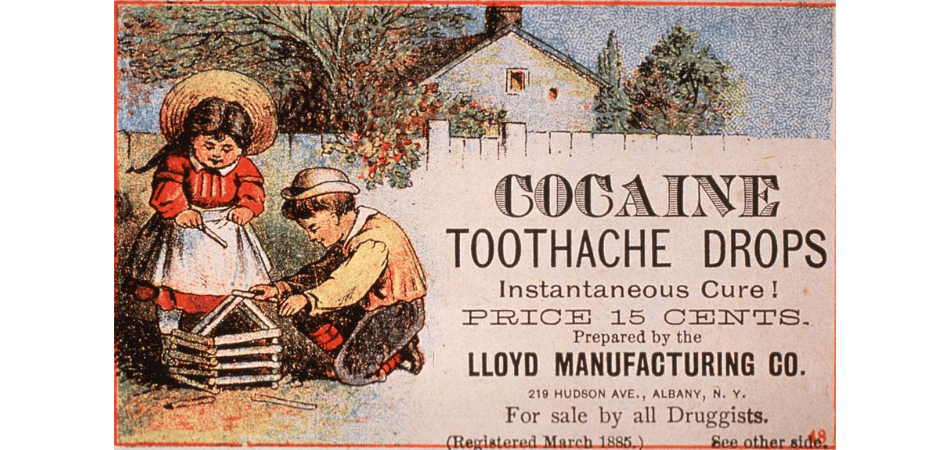

Advertisement for medicinal drops to relieve toothache, Lloyd Manufacturing Co., 1885, National Library of Medicine

The transition from medical to recreational use

The leap from medicine cabinets to mainstream recreational use was swift. By the late 1800s, cocaine had found its way into numerous over-the-counter concoctions, with even the most mundane of ailments being ‘treated’ with a dose of the drug. Cocaine’s prevalence was such that there were even small amounts in the original formula for Coca-Cola.

Before long, cocaine’s ability to alleviate fatigue and heighten alertness made it popular among workers, and it became a fashionable stimulant among the upper classes in the form of tonics, elixirs and the infamous Vin Mariani – a wine that contained cocaine. This positive reputation was further solidified by figures like Sigmund Freud, who extolled its virtues, and even Thomas Edison was rumoured to have partaken to fuel his long hours of work.

Cocaine Papers, Sigmund Freud, 1884

From wonder drug to public enemy

By the early 1900s, however, the narrative had begun to shift, with newspapers reporting stories of individuals who, under the influence of cocaine, exhibited erratic and sometimes violent behaviour. These reports played a significant role in changing public opinion, and cocaine began to be painted as a catalyst for moral decay and social unrest.

The demonisation of cocaine was further exacerbated by racialised reporting and the stigmatisation of minority users. The drug’s prevalence in Southern states led to inflammatory and often unfounded associations with African-American men, falsely accusing them of committing sexual crimes under the influence.

One widely debunked myth was reported by The New York Times in 1914 under the brazenly racist headline “Negro Cocaine “Fiends” Are a New Southern Menace”. According to the article, cocaine made black men impervious to .32 calibre bullets, causing local law enforcement to switch to more powerful calibres. These kinds of racially charged media reports contributed to a mounting hysteria that played directly into the hands of legislators seeking a hardline approach to drug control.

NEGRO COCAINE “FIENDS” ARE A NEW SOUTHERN MENACE; Murder and Insanity Increasing Among Lower Class Blacks Because They Have Taken to “Sniffing” Since Deprived of Whisky by Prohibition., Edward Huntington Williams, M.d., New York Times, 1914

Legislation and the war on drugs

The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914 marked a turning point in America’s approach to drug regulation. Intended to monitor and control the production and distribution of opiates and coca products, it effectively criminalised the non-medical use of cocaine. The Act required prescribers and distributors to register and pay a tax, which created a government ledger of drug transactions and imposed heavy penalties for non-compliance.

The Harrison Act did not outright ban cocaine, but by imposing stringent regulations and hefty taxes, it made non-prescribed use and distribution a prosecutable offence. This legislative measure reduced both the public’s access to cocaine and its use in over-the-counter products, which greatly diminished cocaine’s medical and recreational use.

The Harrison Act was followed by the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1920, which sought to further control the narcotics trade in the wake of World War I. This legislation expanded upon the Harrison Act’s framework, implementing stricter regulations on a broader range of substances, including cocaine, which was made essentially illegal under the Act.

The aftermath and rise of new stimulants

In the wake of the Harrison and Dangerous Acts, cocaine use saw a notable decline. The stringent regulatory measures increased the risks associated with importing, distributing and selling cocaine, which in turn inflated the costs.

Wholesale price of cocaine (per ounce), 1892-1930

1892, 1895, 1897 and 1900 weekly wholesale prices, Oil, Paint and Drug Reporter. 1903 and subsequent years from Mallinckrodt Chemical Works price list.

These drastically higher prices, combined with the increased legal, health and social risks associated with cocaine, deterred many from its use. In essence, by making cocaine less accessible and more expensive, the Act had indirectly influenced the market dynamics, effectively reducing its prevalence in society.

Total manufactured and imported cocaine, 1882-1931 (five-year average)

Weekly New York importation records, Oil, Paint and Drug Reporter, and annual importation records, United States Treasury Department.

Perhaps the best indicator of the effectiveness of the legislation is the decline in the number of people treated for cocaine addiction. For example, patient records from the Keeley Institute, a nationwide network of private treatment centres, show that while 18% of patients between 1837 and 1897 used cocaine, this dropped to 9.7% in 1905, with no cases at all after 1910.

However, with the void left by cocaine’s decline, heroin use increased dramatically in the US while amphetamines began to fill the demand for stimulants. First synthesised in the late 19th century, amphetamines were not widely used until they were reintroduced as a treatment for a range of conditions in the 1930s. Cheaper and more readily available than cocaine following the new legislation, amphetamines saw a swift rise in popularity after their reintroduction.

This shift to amphetamine use illustrated a pattern that has been repeated throughout drug control history: when one substance becomes difficult to obtain, another emerges to take its place.

Reflecting on the past to inform the future

America’s early battles against cocaine provide crucial insights into the complexities of drug control. One of the primary lessons is the significance of societal and cultural factors in both the spread and containment of drug use. The cocaine epidemic and subsequent decline post-legislation underscore how legal frameworks can and do influence drug trends. However, they also reveal that legislation alone cannot be the sole mechanism for control; public education, cultural attitudes and economic factors play equally vital roles.

The Harrison and Dangerous Drug Acts set a precedent for the future of drug legislation, and its echoes are felt in today’s drug policies. Contemporary approaches to drug addiction often focus on a balance between control and treatment, reflecting the understanding that punitive measures must be accompanied by support for those addicted. While stopping the supply can go some way to reduce the prevalence of one drug, without a holistic plan, there is always a new substance waiting to take its place.

Final thoughts

The turn of the 20th century marked a significant chapter in America’s relationship with drugs. From its arrival as a miracle substance to its descent into notoriety, cocaine’s journey mirrored society’s evolving perspectives on substance use. While early 20th-century legislation was temporarily effective in curbing cocaine use, it did not last. By the 60s, cocaine had made a huge comeback, causing major destruction in the lives of users, those involved in the drug trade and innocent people caught in the crossfire of drug wars.

As policymakers and health professionals confront contemporary drug crises, the lessons from America’s first significant drug regulation remain pertinent. The shifting landscape of drug use, the rise of new substances and the ongoing debate over the best approach to drug control reflect the challenges faced over a century ago. Understanding the intricacies of past drug policies and, in particular, where they fall short can provide a blueprint for creating more informed, effective and humane responses in the future.

If you are struggling with cocaine addiction, reach out to UKAT today. We provide comprehensive cocaine rehab and detox services to help you overcome addiction and restart your life.

(Click here to see works cited)

- Das, G. “Cocaine abuse in North America: a milestone in history.” PubMed, 1993, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8473543/. Accessed 8 November 2023.

- Hart, Carl L. “How the Myth of the ‘Negro Cocaine Fiend’ Helped Shape American Drug Policy.” The Nation, 29 January 2014, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/how-myth-negro-cocaine-fiend-helped-shape-american-drug-policy/ Accessed 8 November 2023.

- Markham, James M. “The American Disease.” The New York Times, 29 April 1973, https://www.nytimes.com/1973/04/29/archives/the-american-disease-origins-of-narcotic-control-by-david-f-musto.html. Accessed 8 November 2023.

- PBS. “The Buyers – A Social History Of America’s Most Popular Drugs | Drug Wars | FRONTLINE.” PBS, 2012, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/drugs/buyers/socialhistory.html. Accessed 8 November 2023.

- Spillane, Joseph F. “Did Prohibition Work? Reflections on the End of the First Cocaine Experience in the United States, 1910-1945.” RAND Corporation, 1995, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/drafts/2008/DRU1243.pdf. Accessed 8 November 2023.

- Wielenga, Vicki, and Dawna Gilchrist. “From gold-medal glory to prohibition: the early evolution of cocaine in the United Kingdom and the United States.” NCBI, 18 April 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3681233/. Accessed 8 November 2023.

- Williams, Edward Huntington. “NEGRO COCAINE “FIENDS” ARE A NEW SOUTHERN MENACE; Murder and Insanity Increasing Among Lower Class Blacks Because They Have Taken to “Sniffing” Since Deprived of Whisky by Prohibition. (Published 1914).” The New York Times, 31 December 1969, https://www.nytimes.com/1914/02/08/archives/negro-cocaine-fiends-are-a-new-southern-menace-murder-and-insanity.html. Accessed 8 November 2023.